All over the world is now rising a new perception that mankind history was just one of migrations, never without pain and suffering, violence and injustice that only today get a tentative resolve through universal/pacific settlements of recognitions, repairs and memory celebrating.

Black(s) to the Future : According to you, what is today the new battlefield for the black community, beyond the Hip-hop legacy iconed by its intelligentsia ? To be more specific and perhaps rough… : is still any identity stake out there for the black community or was the melting pot successful enough to forge a new American identity, ready to confront new external threats to its integrity as one people, one nation? This question being all the more decisive as we cannot but take into account loads of “friction points” – among whose the latests, ranging from Cleveland & Baltimore protests to the release of the movie “Dear White People”…

Mark Dery : Since I’m one of the Dear White People, it would be presumptuous of me (in the extreme!) to speak on behalf of African-Americans, much less to draw up a cultural battle plan for black America.

That said, your reference to the politics of black identity makes me think of the striking contrast between the internationalism of black liberation struggles in the past—I’m thinking specifically of W.E.B. DuBois—and the way that today’s direct actions for civil rights, social justice, and freedom from fear—massive street protests, the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, the “I Can’t Breathe” meme, Bree newsome shimmying up the flagpole at the South Carolina state Capitol and hauling down the Confederate flag—are taking place, in the United States, against a slow-rolling assault on the gains of the civil-rights era and a societal trend toward the island self.

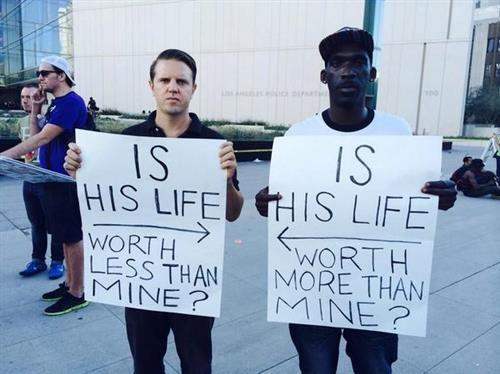

Two demonstrators following the riots in Ferguson, opposed to the systemic violence faced by Africans Americans (source : @occupythemob on Twitter )

By “slow-rolling assault,” I mean the gutting of the Voting Rights Act, widespread voter suppression, gerrymandering (tactical redistricting to weaken the political impact of communities of color), the criminalization of the poor, the mass incarceration of young black men by the prison-industrial complex and, not least, the brutalization and murder, more often than not with impunity, of black people by an increasingly militarized police force whose real job is to protect the property and peace of mind of the ruling class from an increasingly discontent underclass. So there’s that, on one hand. And on the other there’s a growing focus on the self.

It’s most evident in the narcissistic Culture of the Selfie normalized by social media. But it’s also clear for all to see in the prevailing presumption, on college campuses, that professors like Laura Kipnis at Northwestern University, who challenge students’ cherished beliefs, are a threat to the notion that the classroom should be a “safe space,” free from unsettling ideas. We can also see this closing down—this fixation on the social atom, the Me who is the measure of all things—in the furor over “trigger warnings,” which again attempt to police professorial speech on the assumption that students who’ve been traumatized by sexual violence will be re-traumatized by, say, a discussion of a novel touching on the theme of sexual violence. And then there’s the notion of “microaggression”—the little, unconsidered racist, homophobic, or transphobic words and deeds that, we’re told, inflict the death of a thousand cuts on people of color, gays, and transgendered persons. This zooming in on the politics of the individual, away from any sense of common cause, and this emphasis on the politics of emotions—giving and taking offense, hurting and being hurt—is at least partly the unhappy fruit of the academic fad, in the ‘90s, for identity politics.

I don’t mean to make light of this heightened awareness of the politics of everyday life, nor to dismiss the million little ways in which power is strategically deployed. But the historical movement away from a wide-angle DuBois-ian internationalism to a politics that zooms in on the individual, focusing on micro-political issues related to the self and the body, strikes me as a capitulation to the status quo.

It’s the politics of cynicism and exhaustion—understandable, in light of widespread feelings of powerlessness in the face of the hollowing out of democracy by corporate influence and billionaire ideologues like the Koch brothers, with plenty of help from the Supreme Court, but hardly helpful. It’s a retreat from the battlefield, in the same way that the Me Generation of the 1970s, with its retreat into New Age spirituality, the self-help and “human potential” movements, and the pleasure domes of swingers’ colonies and gay bathhouses was partly a concession of defeat in the streets at the barricades, even as it pushed the envelope of social change by challenging normative notions of gender and sexuality. Of course the personal is political, and of course the relatively sudden about-faces on gay marriage and transgender acceptance (at least, in the case of famous transwomen like Caitlyn Jenner, whose cheesecake cover for Vanity Fair ironically reaffirmed notions of conventional femininity and beauty) are thrillingly liberatory, an all too rare sign of human progress.

The culture wars matter, obviously. But so do collective demands for legislative and judicial change, and grassroots action for social justice, and the tearing up of deep-rooted institutional evils. It’s not a zero-sum game, but a lot of us dream, I think, of the rise of a mass movement demanding social justice and economic equity by any means necessary. That’s the black future I hope I live to witness.

It’s not my place to say what black America should do, but every time someone like Ta-Nehisi Coates or Cornel West or Robin D. G. Kelley or Tricia Rose or Mychal Denzel Smith or Greg Tate or Michael Eric Dyson or Mark Anthony Neal speaks truth to American power, it practically makes my hair stand on end. It makes the Matrix glitch, if only for a flickering second, giving us a glimpse both of the Nightmare of the Real and of utopian possibilities that could be ours for the grabbing, if we had the collective will.

Read the first part of our interview w/ Mark Dery

Read the third part of our interview w/ Mark Dery

Read the last part of our interview w/ Mark Dery

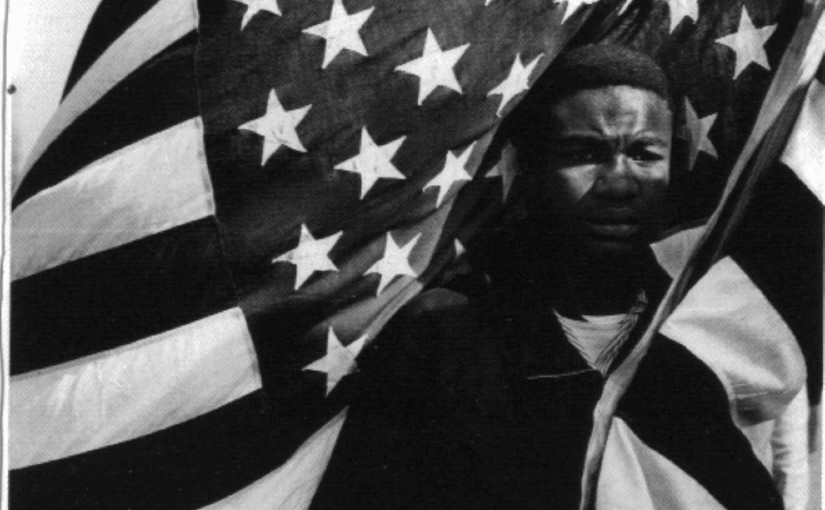

Cover photo :

Civil Rights photograph series, by James Karales

3 comments