As such, it embodies a budding counter-power ; leaded by afro-related figures (which is already a toppling in itself) but truly – and deeply – soaking every operating subversive proposals and transcending all our points of reference : identity, time and space.

Aliens, graffiti, superheroes, time travel, and… Erykah Badu? How do they fit together? Why [are] they together at all? | That’s what is so intriguing about the concept. It can’t be limited. Afrofuturism draws in elements from all aspects of culture. | It was coined by Mark Dery in his 1994 essay, “Black to the Future,” in which he defines it as, “Speculative fiction that treats African American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of twentieth century technoculture– and, more generally, African American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future.” | Over two decades later, Dery’s definition seems way too restrictive for today’s wave of afrofuturism. | Afrofuturism explores the future in a black context, incorporating technology and fantasy to provide an escape from the oppressive past and ailments of the present through music, visual art, and literature. According to author Ytasha Womack, “Afrofuturism bridges so many aspects of our culture, from African mythology, art and hip-hop to politics, comic books and science.” Afrofuturism is everywhere. Daja Henry

So it is obvious that afrofuturism originates from Afro-American voices, as the standard-bearer of black people fight emancipation, between the recall for a forgotten/despised legacy, the struggle for a present-time acknowlegdment and the attempt to impose its right to be as equally part of future forecasts.

In an essay found on the Sun Ra Arkestra website by Stefany Anne Goldberg, she sites, “I didn’t find being black in America to be a very pleasant experience,” said Sun Ra, “but I had to have something, and that something was creating something that nobody owned but us.” She also mentions, “African-Americans had always been a secret society within greater American society, with their own music, their own language, their own rituals. This secret history could be an asset for African-Americans in the Space Age to come. African-Americans could re-invent their past and create a futurist Utopia, perhaps on a planet other than Earth, which seemed to Sun Ra unbearably steeped in chaos and confusion.” Jeffrey Vinson

However, precisely because it is (above all) a forward-looking process, Afrofuturism goes beyond its own definition : it relies on the stretching of its own limits. Both in order to escape any attempt to fix it in a place it wouldn’t have chosen for itself, but moreover because it is an inherently adaptative network of ideas, inspirations and proposals. Thus it continuously challenges its laurels and metamorphoses.

Afrofuturism is built on people remaking perceptions of themselves and an awareness of their power,” [Mantse] Aryeequaye says, in an all-embracing description. Billie Adwoa McTernan

The main idea to understand about Afrofuturism is that it proposes a journey to an always unexpected otherwordlyness. And so doing, it redefines both our relationship to time and humanity… the two bases of our world.

Time

The time structure of Afrofuturism is even more intriguing than wormholes’s. It doesn’t distort time, or expand it : it dismantles it. Afrofuturism refutes linearity. It comes and goes, forcecasts and alterates… both the past, the present and the future.

It doesn’t deny its historical background, however it doesn’t settle for it either. (Which is all the more understandable when considering how unsatisfactory Afro-American history is in many ways). Though, it recomposes from it, drawing it to its own narration.

KLG: […] Though Fanon certainly warns us not to become slaves of slavery, it’s pretty clear to me that questioning tomorrow would be an empty practice in the absence of dialogue with uncomfortable yesterdays. […] I suppose what I’m getting at is the fact, as Glissant suggests, that we can — we must — revisit past narratives prophetically; we must reimagine the “same old” stories differently, with an eye to the present and to the futures we desire. Didier Sylvain [to Kaiama L. Glover]

As for what has to do with the present/future couple, it encloses it the same way. It uses the power of projection in order to modify the current flow of things. And the other way round, it proposes alternative lectures of the present time in order to reshape the future.

Afrofuturism creates a space for those from the Black Diaspora to explore issues in the present and how they will manifest in the future. As Michah Yongo points out, just as the language used in Orwell’s 1984 has been used to frame the debate around increasing government surveillance, black science fiction can provide a new language to address the increasingly complicated frameworks of discrimination. If we are able to name these frameworks in the same way we recognise Big Brother when we see him, it is the first step in being able to dismantle them. In this sense, Afrofuturism provides a lot more to the black experience than simple escapism, silver Dashikis and pyramid-shaped spaceships, although I will always have time for that too. Chardine Taylor-Stone

Time defines a connection between “us” (humans) and what surrounds us. So by reshaping it, Afrofuturism impacts the way we relate to the world (eg. considering future impacts instead of immediate advantages). It isn’t enough though : it is also crucial to reinvent how we relate to each others and what we think each others are or could be… which is the second “act” of Afrofuturism ; since its very beginning.

Humanity

Black people have always embodied the shortcoming of a conventional definition of what it is to be a – rightful – human being. From slavery to nowadays (and still too many tomorrows to come…) ; they’ve continuously had to give proof of their legitimacy to be considered as such. First literally, but later on (and still today) regarding their rights to claim for the same treatment as all other agreed-to-be persons.

[Marlo David, in an essay titled “Afrofuturism and Post-Soul Possibility in Black Popular Music”] posits that the idea of humanism has “come under suspicion for its hegemonic assertion of Enlightenment ideals of the liberal white male.” This is why even though Africans are human; we must define what an Africana humanity is. Jasmine Nelson

This is why, afrofuturism came with a variety of speeches according to which black people wouldn’t be humans, as regard to the official label of what it supposedly means.

African Americans are – in a sense – the descendants of alien abductees, in that they’ve been taken from a place, and transported to a new place with rampant discrimination and restrictions. Ashley Clark [to Shane Thomas]

The “android” is [also] a frequented term used in Afrofuturism. […] Despite its physical appearance, the android is not human [, they] are programmed starting from birth to perform [: rights dependent upon race, gender or class are assigned […] Jasmine Nelson

This said, Afrofuturism made a strengh out of this non-conformity : africana wouldn’t – have to – be at the mercy of a defining system (based on them not belonging to it in the first place) only. They could transform the shameful inexpediency into a proud self-distinction. Afrofuturism would welcome differences instead of classifying them and making them compete.

KLG: […] like Fanon and Glissant and others, [Alexander G. Weheliye, in the context of a symposium about Afrofuturism] rightly understands and foregrounds the relational nature of our being-in-common – our imperative to acknowledge the various iterations of our (social) difference and the ethical practice of being decent to one another in the face of this diversity. To me, that’s what an Afro-futurist humanism looks like. Didier Sylvain [to Kaiama L. Glover]

Therefore, if Afrofuturism would stand for a mean of empowerment for black people, it would greet them beyond any gender/social, origin/geography, belief/will discrimination… And by doing so, it would become an inspiring (maybe the utmost) inclusive model for all those who do not “fit”.

The power play

Inclusiveness is certainly one of the key features of Afrofuturism. This is how and why it might be considered as a potential challenger of the system. It started because of it and expanded within it, but it foils it every time it wants to contain it : it is slowly absorbing it.

Not to do its key practitioners a disservice, but afrofuturism’s nebulous nature is one of its strengths. It’s not something that can be co-opted at the moment. It’s not one dance move, it doesn’t have one singular practice that a ‘Johnny-come-lately’ can pick up on, and I think that’s something to be cherished. It’s an emerging movement, but afrofuturistic ideas existed long before the term was coined. Ashley Clark [to Shane Thomas]

[Yet, more than ever] that message of self-awareness, free expression and empowerment still exists in modern Afrofuturism, which has produced one artist credited with taking its ideas into the mainstream [: Janelle Monáe .] Ytasha Womack sees Monáe’s art as being able to transcend racial boundaries, taking Afrofuturism away from being a purely black concept. […] “A lot of people can associate with this concept of otherness for a whole host of reasons, many of which are not racial, so there’s a connection there.” [This said, she isn’t the only one, now or to come.] That cross-fertilisation of ideas has always been central to Afrofuturism and helps to answer a question Dery asked when he first coined the term: “Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?” Twenty years on the answer is an unequivocal “yes”, and now the question seems to be where their imaginations and mutations will travel next. Lanre Bakare

For more infos or details :

Daja Henry, Afrofuturism : “Black to the Future” and Beyond (June 13, 2015)

Jeffrey Vinson, I Am Not A Human Being: Afrofuturism in Pop Culture (April/May, 2015)

Billie Adwoa McTernan, Afrofuturism: Seeing parallel worlds | East & Horn Africa (July 20, 2015)

Didier Sylvain to Kaiama L. Glover, Tomorrow is the Question: Afrofuturism and engaging prophetically with history (March 12, 2015)

Chardine Taylor-Stone, Afrofuturism: where space, pyramids and politics collide (January 2, 2014)

Jasmine Nelson, Black Futures Matter: Redefining Afrofuturism (May 11, 2015)

Ashley Clark to Shane Thomas, Inside Afrofuturism: This movement is not for co-opting (November 14, 2014)

Lanre Bakare, Afrofuturism takes flight: from Sun Ra to Janelle Monáe (July 24, 2014)

Photo credits :

Cover : Black Radical Imagination, 2014’s edition, “Afrosurreal”

Yinka Shonibare MBE, in collaboration with The Fabric Workshop & Museum, Space Walk, 2002

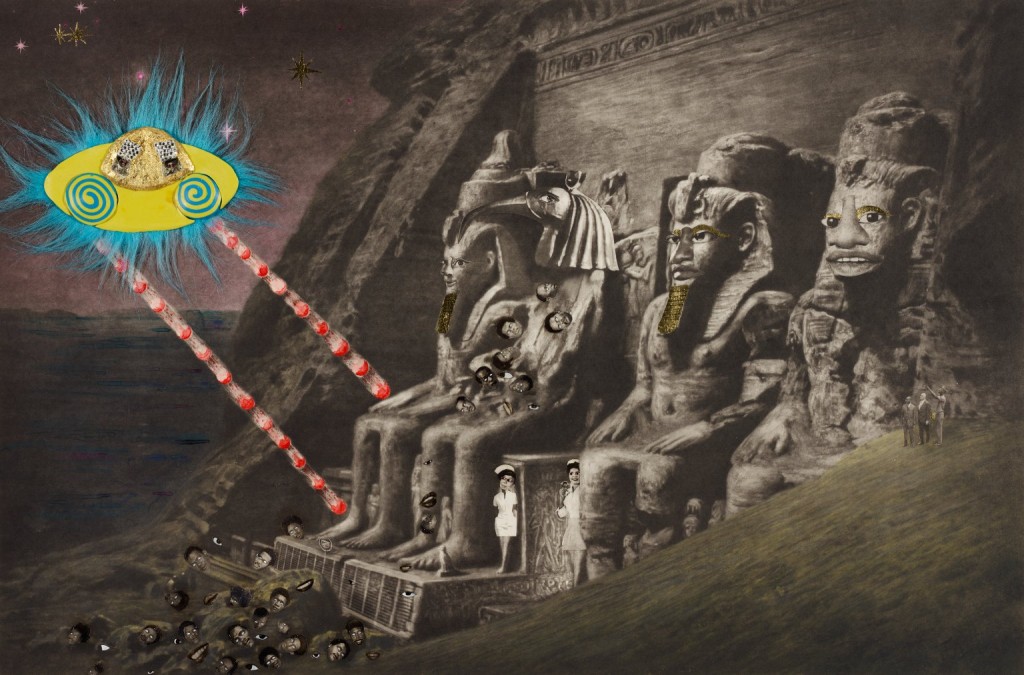

Ellen Gallagher, Abu Simbel, 2005

Paweł Althamer, Wspólna sprawa (Common Task), 2008

Faranú, untitled (sculpture), 2010